A History of Texas Agriculture

The land has always been central to Texas’ identity. The opportunity to cultivate new land first attracted the settlers who would eventually launch the Texas Revolution. The opening of the cattle trails would transform Texas into one of the biggest cattle producers in the world and instill the image of the cowboy in the world’s imagination.

In many ways, the history of Texas’ growth is the history of agriculture. Here’s how it all began, along with some of the changes that helped shape Texas agriculture into what it is today.

Precolonial and Spanish Texas

Texas’ geography is vast and rugged, its climate severe and unpredictable. Before European settlers, most of the peoples who lived in what we now call Texas were hunters and gatherers — nomadic tribes who lived off the abundant herds of wild buffalo or foraged for game and wild edible plants, fruits, and berries.

There were a few agriculturally based societies of indigenous Texans. The Caddo Indians in East Texas, for example, lived in villages and cultivated corn, beans, and squash.

The arrival of Spanish settlers and missions began to change the way Texas’ inhabitants interacted with the land. The Spanish introduced livestock — particularly cattle, sheep, goats, and hogs. Mission settlements were not merely ways to spread Spanish political influence and the Spanish Catholic faith into Texas; they also brought new ideas about how to cultivate crops and raise livestock, including the introduction of irrigation ditches. But the impact of Spanish settlers was limited because most of the state was still dominated by Comanche and Apache tribes, which contained the Spanish foothold in Texas.

Early Texas

Like so many Americans who moved westward across the continent in the 19th century, the first Anglo settlers were drawn to Texas by the promise of abundant land. Newly independent Mexico offered land grants to anyone interested in cultivating its large and sparsely inhabited northern region. Stephen F. Austin led 300 families from the U.S. who settled and introduced a slave-based cotton-plantation system, essentially using the new land in Texas to extend the agricultural practices of the American south. In addition to new plantations, the early Texans expanded livestock cultivation and established small working farms.

After the Texas Revolution, the cultivation of the state evolved quickly. Cattle drives were established, bringing cattle to market in New Orleans and Fort Smith, Arkansas. Cotton production expanded, particularly in the South-Central region around the Brazos, Colorado, and Trinity river basins. And new immigrants — particularly Germans and Czechs — established smaller, subsistence farms.

Cowboys and King Cotton

After the Civil War, Texas’ cotton plantations transitioned from slave labor to tenant farmers, though for many, the transition didn’t mark a significant change in their living situation. While, theoretically, the tenant farmers received a share of the proceeds of the crop for their labor, the system often left farmers indebted to landowners and effectively tied to the land. Cotton became Texas’ major cash crop, and the expansion of the railroads helped expand the state’s reach to markets for the crop.

In addition, commercial farms began producing wheat, rice, sorghum, hay, and dairy in the latter half of the 19th century.

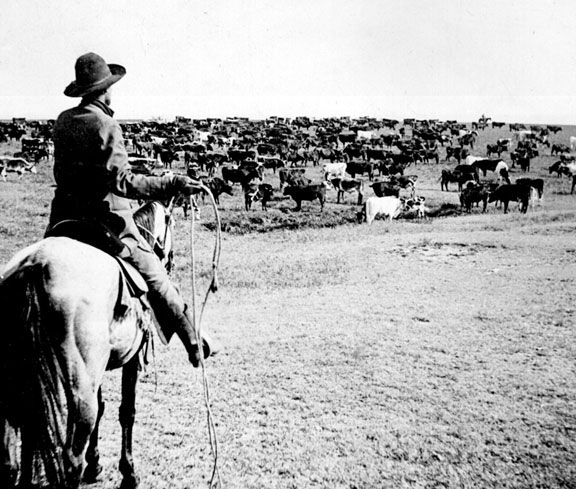

But no innovation impacted late-19th-century Texas agriculture like the emergence of the cattle industry. After the Civil War, the Texas Rangers and the U.S. Army forced Comanche, Apache, and all other remaining tribes onto reservations, thus opening the vast expanse of Texas’ west for settlement and ranching. Legendary Texas ranchers like Charles Goodnight, William T. Waggoner, C. C. Slaughter, S. M. Swenson, and William D. and George T. Reynolds gobbled up huge tracts of land and opened new trails to drive cattle to market.

Into the Modern Age

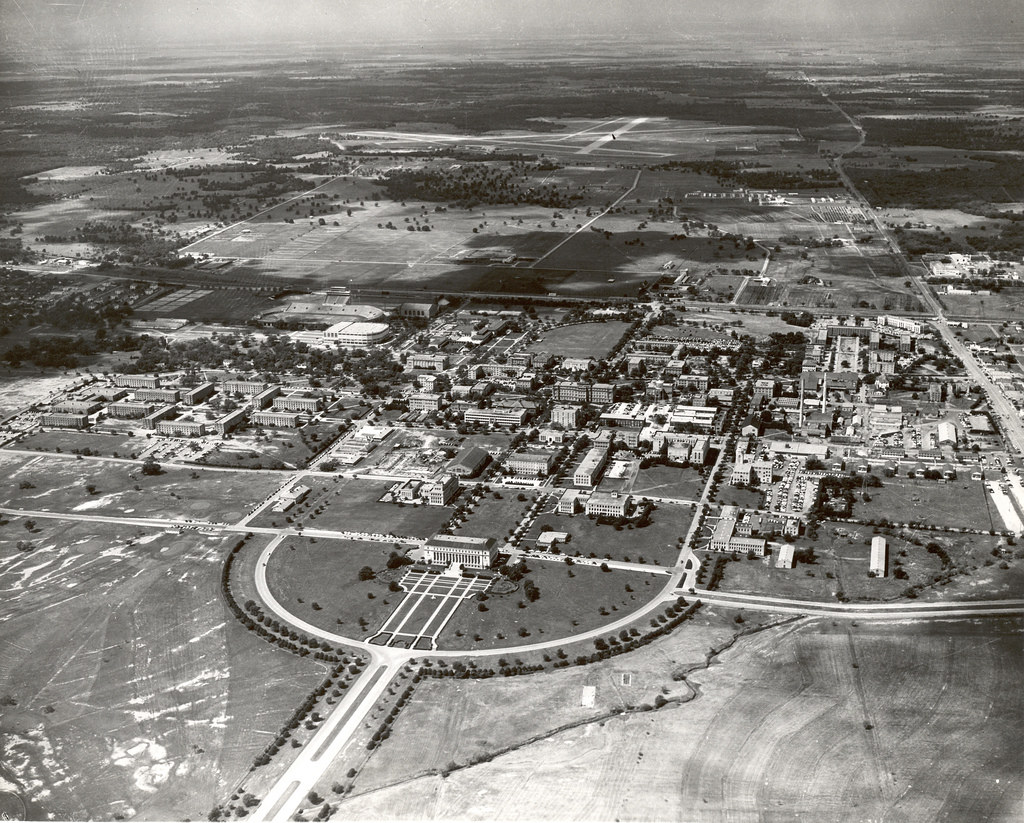

The first step toward the modern era of Texas agriculture was taken in 1876, when Texas A&M University opened. The university would be pivotal in advancing the science and research around agricultural practices in the state.

The school’s first big impact came when scientists at A&M helped eradicate Texas fever, which had devastated the cattle industry. By the turn of the century, new approaches to agriculture drove an industry that was responding to the rapid growth of Texas cities and the need for food and other agricultural products to support them. Between 1900 and 1920, the amount of cultivated land in Texas grew from 15 to 25 million acres.

During this time, cotton production increased, as did corn and rice farming. The Rio Grande Valley evolved into a productive citrus region, as the river was harnessed to irrigate the arid land. The Panhandle and high plains also emerged as a productive cotton-growing region, as irrigation practices were extended to the region and scientists adopted varietals to withstand the harsh climate.

By the 1920s, the future of Texas agriculture had taken shape. Seventy percent of the state’s agricultural land was used for livestock, and nearly 20% of the land was used for growing crops, with cotton dominating.

Present Day

The geographical diversity of the state has allowed for successful production of a great range of crops — from tomatoes in South Texas to rice in the southeast to corn in the northern plains — that have helped sustain Texas as one of the great agricultural producers in the U.S.

Learn how our amazing Texas Farm Bureau members continue to innovate and bring Texas’ agricultural practices into the future.

© 2020 Texas Farm Bureau Insurance