Admiral Nimitz: Texas Hero on the High Seas

On Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese planes swooped down on the U.S. naval base in Pearl Harbor and bombed the U.S. fleet, drawing America into war. The Japanese sank or destroyed six U.S. ships and killed 2,403 Americans. Before the fires were extinguished in the harbor that day, the Navy knew it needed to replace the command of the Pacific fleet with someone who could restore the naval fleet and lead America into war. President Franklin D. Roosevelt turned to a 56-year-old Texan from Fredericksburg named Chester W. Nimitz.

Nimitz’s career in the Navy had been somewhat unconventional. Court-martialed early in his career for running a destroyer in his command aground, he subsequently found success as a commander of submarine divisions. What his superiors recognized in him after Pearl Harbor was a decisiveness and optimism that would prove vital to his leadership during the war. These were values instilled in Nimitz during his youth growing up in Texas when life was still lived at the perilous edge of the frontier.

Here’s a look at Nimitz’s life and how this Texan changed World War II’s Pacific theater.

German Roots, Texas Blood

Landlocked Fredericksburg may seem an unlikely place of origin for a great naval hero, but Chester Nimitz came from a maritime family. Nimitz’s father died before he was born in 1885, and for the first six years of his life, he was raised by his mother and grandfather in the Nimitz Hotel in downtown Fredericksburg.

Before emigrating to the U.S. — and eventually Texas —Nimitz’s grandfather had spent time serving in the German merchant marine. The Bremen, Germany-born man had founded the Nimitz Hotel after moving to Texas, and the hotel hosted notable guests, such as President Rutherford B. Hayes, Robert E. Lee, Ulysses S. Grant, and many others.

Nimitz’s family in Fredericksburg, however, was by no means well-off. To help his mother make ends meet, young Chester worked as a handyman in his uncle’s hotel in Kerrville. By his teenage years, Nimitz knew he would not be able to afford a college education, so he decided to pursue military service.

He had wanted to study at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, but all the congressional appointments to the military academy were spoken for. There were appointments available to Texans interested in the Navy. Nimitz attended the United States Naval Academy and graduated seventh in his class in 1905.

Navigating a Naval Career

Soon after graduation, the young naval officer was handed command of a gunboat in the Philippines, followed by a destroyer, but after he ran the ship aground, Nimitz was court-martialed and reassigned to a submarine. Submarine duty in the early 20th century was certainly a demotion. The cramped, dangerous vessels were still in their technological infancy.

However, Nimitz excelled in his new command, and his experience with submarines would become vital, as the ships played an increasingly important naval role in the first and second world wars.

Nimitz continued to build on his experience in the leadup to the two wars. He spent time studying diesel engines in Germany and Belgium and oversaw the construction of the first U.S. Navy vessel powered by diesel.

During World War I, he served as submarine commander and was promoted to chief of staff to the commander of the Atlantic Submarine Force. After the war, he helped build the submarine base at Pearl Harbor and participated in mock Pacific-war exercises to plan for a hypothetical naval war in the Pacific.

Nimitz couldn’t know it at the time, but the Pacific war plan he helped draft would eventually be the strategy he employed in the war against Japan.

Taking Command of the Pacific

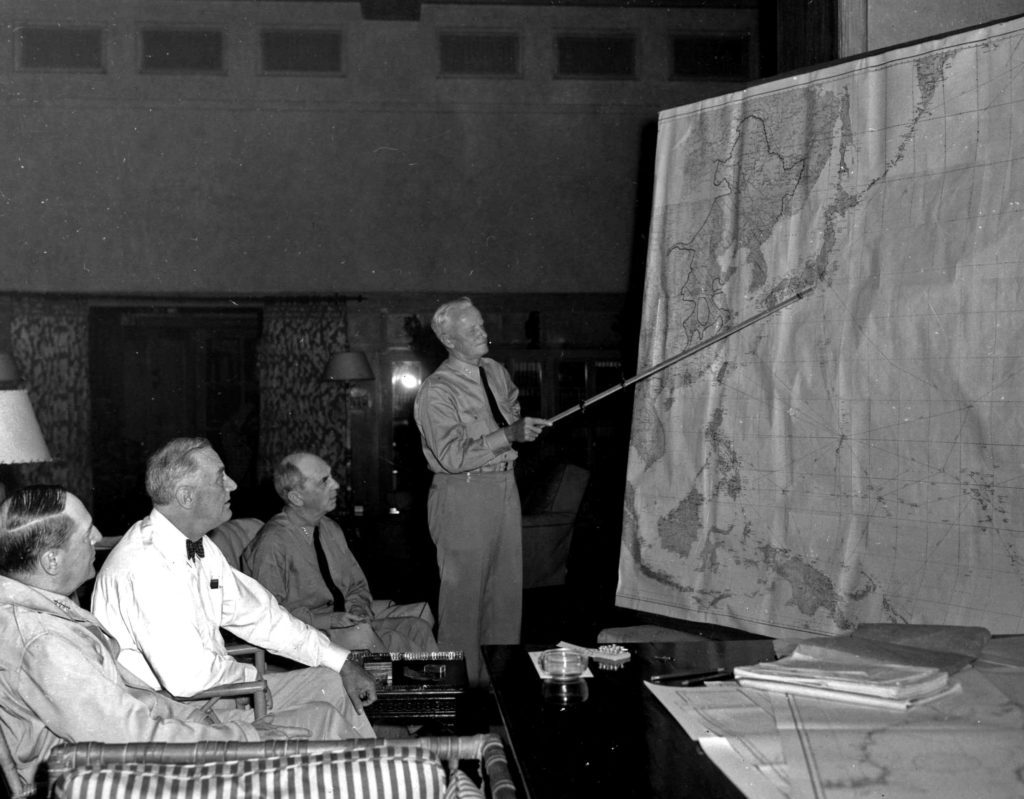

When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Nimitz was serving as the Navy’s chief of the Bureau of Navigation. Ten days after the attack, President Roosevelt promoted him to commander in chief of the United States Pacific Fleet, skipping the rank of vice admiral by congressional appointment.

It soon became clear why Roosevelt turned to Admiral Nimitz to lead the U.S. war effort in the Pacific. He was described as serene and clearheaded and earned the trust and loyalty of his staff. Rather than replacing the staff of his predecessor, when Nimitz became admiral, he kept them on and helped rally morale.

“I know we are suffering, but I promise you the enemy is suffering too,” he told them.

Rather than dwelling on the devastated state of the U.S. fleet, Nimitz pointed to three mistakes the Japanese had made in the attack: They attacked on a Sunday when most crew were ashore; the bombers focused on sinking ships but didn’t destroy the dry docks the U.S. could use to make repairs to damaged vessels; and they had failed to destroy the Navy’s entire fuel supply, which sat in tanks 5 short miles away from the harbor.

Privately, however, Nimitz revealed his trepidations at the outset of war. On Dec. 19, his wife wrote a letter reminding him that he had always wanted to take command of the Pacific fleet; that it was the “height of glory.”

“Darling,” Nimitz replied. “The fleet is at the bottom of the sea. Nobody must know that here, but I’ve got to tell you.”

A Texan at War

Nimitz’s optimism, despite his misgivings, and his level head helped set the tone for the Pacific theater. A key early victory at Midway Island set the U.S. Navy on course to victory. The campaign was unlike any that had been attempted in human history, with a sea and land war waged across an incredibly vast area, covering thousands of square miles of ocean and hundreds of islands large and small.

Throughout four grueling years, Nimitz’s Navy would help beat back Japanese forces and regain control of the Pacific. After the second of two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan in August 1945, the Japanese surrendered.

On the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on Sept. 2, 1945, Nimitz signed his name to the treaty as the U.S. representative to the formal surrender of Japanese forces.

Now the Fleet Admiral — a lifetime appointment by President Roosevelt — Nimitz stopped serving with the Navy two years after the end of the war but continued his public service as a roving ambassador for the United Nations, regent of the University of California, and chairman of the Presidential Commission on Internal Security and Individual Rights under President Truman.

In 1966, Nimitz suffered a stroke, and he passed away in February of that year. He is buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California.

Fredericksburg Honors a Hometown Hero

In 1964, Fredericksburg citizens decided to honor their neighbor who had become a hero of the second World War by turning his grandfather’s historic Nimitz Hotel into a memorial and naval museum.

Throughout the decades, the museum has evolved into the National Museum of the Pacific War, featuring 55,000 square feet of exhibit space that interprets the history of both the Pacific theater of the war and the Fredericksburg native who led Navy forces.

In 1976, the Japanese government gave Fredericksburg and the museum a Japanese peace garden to celebrate the small Texas town’s 130th anniversary. This year, the old hotel will reopen after extensive renovations to the exhibition that tells the story of the incredible life of Admiral Nimitz.

Today, the museum does more than honor one of Fredericksburg’s most notable sons. The museum is an education and research center that contains manuscripts, documents, photographs, and interviews with Pacific war veterans that are invaluable to researchers and historians of World War II.

Travelers through the little town may find it odd that such a monument to the U.S. Navy sits so far from the coast. It is a reminder of the twist of fate that once sent a son of German immigrants from the hills of Texas to the U.S. Navy, so that he could forever change the course of history.

For more Texas history, check out this guide to the historic forts trail.

© 2020 Texas Farm Bureau Insurance