Alone on the Range: The Story of the Bison at Caprock Canyon

There was a time when bison covered the prairie landscape of the American West. The herds in today’s Texas numbered an estimated 30 to 60 million at their peak. They were so plentiful, in fact, that early Spanish explorers noted they were like “fish in the sea.”

Bison are a keystone species in the prairie ecosystem, which means they played a pivotal role in the healthy functioning of the Great Plains habitat. Their migrations and grazing allowed for fauna and flora to flourish by reducing dead vegetation and allowing for new growth. This, in turn, allowed other species to find the food they needed and thrive. Bison were such a central part of the culture of the Indigenous peoples of the Texas prairie that they are incorporated into their myths and legends.

That makes the story of the American bison all the more tragic.

After the Civil War, as settlers began to push westward in greater numbers, bison became a target. Bison were a source of food for these settlers, but more significantly, they became tools in a genocidal warfare. Bison were so vital to Indigenous peoples that clearing the land of bison became a key component of the genocidal strategy of clearing the land of its native inhabitants. Thus began what is now known as the “great slaughter.”

The Clearing of the Prairie

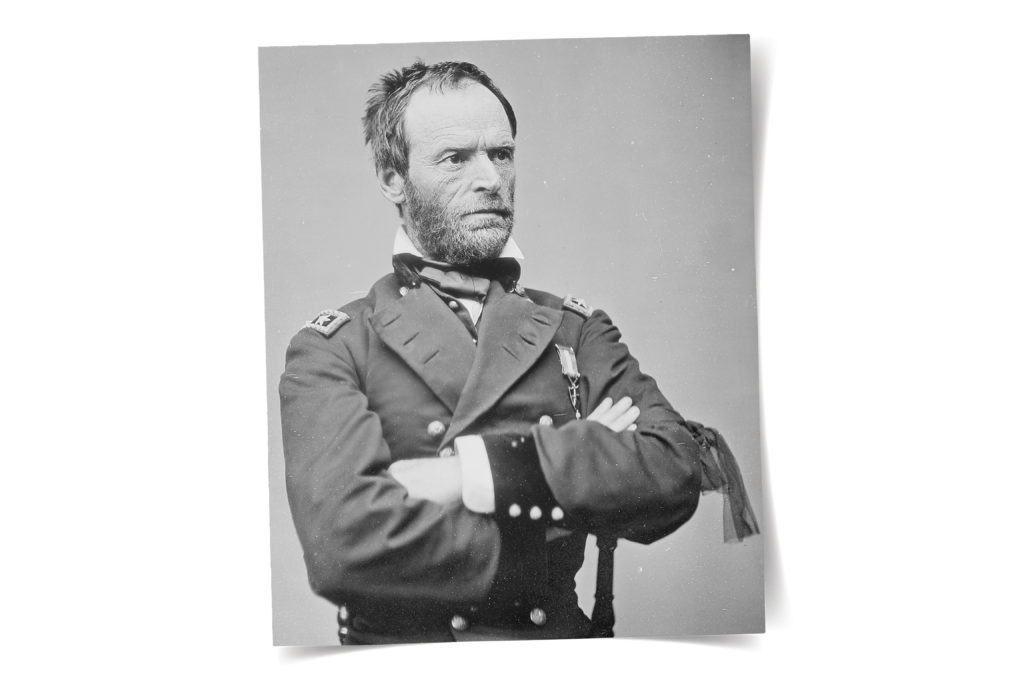

In the years following the Civil War, the U.S. military sent West to ready the frontier for expansion were commanded by Generals William Tecumseh Sherman and Phillip Sheridan. This was the same General Sherman who brought a cruel end to the Civil War by employing a “scorched-earth” strategy to the South with his armies burning, demolishing, and sabotaging their way in the march to Atlanta. He would advocate for a similar approach in the West. In a letter from Sherman to Sheridan in 1868, Sherman observed that as long as bison roamed the plains, the U.S. military and settlers would come into conflict with Native Americans. “I think it would be wise to invite all the sportsmen of England and America there this fall for a Grand Buffalo hunt,” Sherman wrote, “and make one grand sweep of them all.”

Beside the ambitions of Manifest Destiny, there was a financial incentive to the hunt. Around 1870, a bison hide could fetch around $3.50 on the market (nearly $80 today). Relatively easy to stalk and hunt, they could be taken with a round of ammunition that only cost 25 cents (or less than $6 today). “Every time I fired,” one frontiersman reportedly said, according to The Atlantic, “I got my investment back twelve times over.” Within months, the race was on, urged on by an economic depression in 1873 that saw many more people heading West looking for an easy way to make a buck.

Thousands of bison hunters arrived, most able to kill 50 a day. Trains passing through the prairie would have men hanging out of windows with rifles, shooting at the bison as they passed. So many bison were killed that the market for hides dropped — but that didn’t stop the killing. Bison were shot and left to rot on the ground. Where the sight of a buffalo herd once symbolized the open frontier, now the bison skull became the American West’s iconic symbol. By 1888, it was estimated that a mere 1,000 bison remained in North America.

Attempts to Save a Species

The sheer scale of killing eventually pricked the moral consciousness of some Americans. In 1875, Congress passed a bill attempting to protect the buffalo, but President Ulysses S. Grant would not sign it. A few western ranchers took pity on the orphaned calves. Among them were Charles and Mary Ann Goodnight. In 1878, the Goodnights herded some orphaned calves and let them roam on their land. These calves would become the core of the Goodnight Herd, and within a few years, it grew to 200 strong.

Mary Ann Goodnight could not have known the full scale of her service to conservation when she urged her husband to protect the bison calves. The Goodnights were one of only five ranchers who protected small herds of bison. Today, those five herds make up the foundation stock of all the bison that remain in North America. Without them, the American Bison would have been lost forever.

The Texas State Bison Herd

The Goodnight’s conservation efforts were largely forgotten for over 100 years. Then, in the late 20th century, wildlife conservationist Wolfgang Frey learned about the bison that still roamed on the JA Ranch and reached out to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department to study the animals. They learned, through genetic testing, that the bison descendants of the Goodnights’ herd were perhaps the last remaining Southern Plains bison. Plans were made to conserve the species and ensure their survival.

The JA Ranch donated the herd to Texas Parks and Wildlife, which moved them to Caprock Canyons State Park in 1997. The preserved prairies of Caprock Canyon allowed the herd to return to some of the last remaining untouched acres of habitat their ancestors once roamed across for thousands of years.

Today, the Caprock Canyon bison herd plays an important role in the ongoing conservation of the American bison. The goal of the state’s bison conversation is to reestablish the bison as the keystone species within the Texas prairie ecosystem. Park visitors can encounter these large, majestic creatures that once teetered on the brink of extinction but are now celebrated as a central part of the history and heritage of the West.

Visiting the Texas State Bison Herd

Caprock Canyon’s raw beauty makes it a great place for hiking, camping, and experiencing the native Texas Panhandle ecosystem, as it has existed for thousands of years. Visitors can also encounter the Texas State Bison Herd.

When you visit, keep in mind a few tips from the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department:

- Keep your distance: Never get closer than 50 yards from the herd.

- Stay calm and quiet: Loud noises and sudden movements can disturb the bison.

- Bison have the right of way: Even though there are roads through the park, this is their habitat. Drive slowly, and if you encounter a bison in your car, stop and let it pass. Never honk or tailgate a bison.

- Learn some bison: Look for signs of agitation to ensure you are not disturbing the herd. A raised tail, ground pawing, or lowering head are all signs that the bison is agitated.

Read the story of how one Texas rancher is protecting the land today.

© 2023 Texas Farm Bureau Insurance